Gea

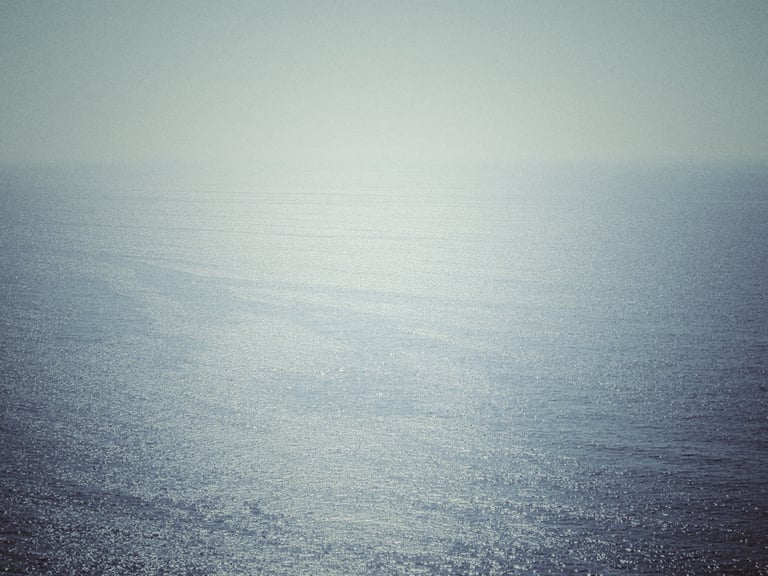

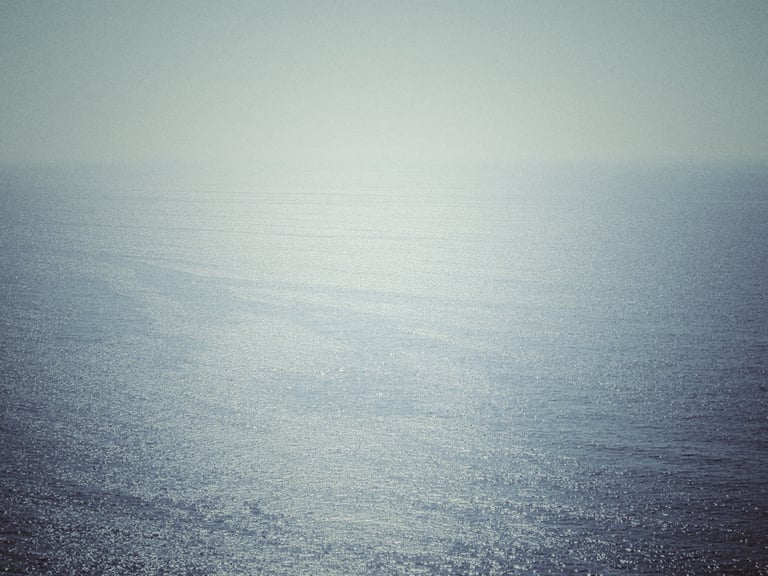

The series Gea takes its title from the ancient Greek goddess of the earth, yet this is not a study of abundance or fertility. Instead, it presents us with landscapes emptied of human presence, where sea and land meet in conditions of low light—in the winter cold, the summer dusk, at moments when visibility fades and the world becomes less certain. There is a stricter, more enigmatic aspect of the natural world on display—one that exists independently of human presence and continues to persist on its own terms.

The work is defined by its engagement with threshold states: the last light before darkness, the boundary between water and shore, the traces left behind after departure. The images seem to emerge from atmospheric instability—approaching clouds, the setting sun, the moment day transitions into night. These transitional moments, often overlooked as mere "in-between" states between more "significant" points in time, take center stage here. In these conditions, any drama fades toward a particular quality of stillness, toward a silence that allows the primal elements to come forward.

The management of light is crucial to the work’s emotional range. Rather than the warmth of the "golden hour," the images reflect a cooler and more ambiguous illumination. The final rays touching the crests of waves, the diffused glow through the clouds—these create images that hover between presence and absence, revelation and concealment. There is a deliberate avoidance of the spectacular; light is not used to emphasize or dramatize, but to imply, to suggest, and to leave questions open. The ocean appears as force and volume, its movement constant and indifferent—a rhythm that predated and will outlast human timekeeping. Here, the sea is not a backdrop but a presence—a reminder of the forces that shape the planet on scales of time and space that transcend human perception.

The absence of people is conspicuous and intentional. Where signs of human presence do exist, they appear suggestively rather than explicitly—footprints in the sand, the arrangement of objects on a beach, a solitary shadow. These traces suggest the current emptiness, creating a temporal layering that resonates throughout the series.

There is a meditative quality to the project’s approach, a deliberate slowing of pace that invites deep observation. This is landscape photography stripped of the "impressive," offering instead a contemplation of place as something larger and more enduring than our own passage through it. The composition is often simple, almost austere, allowing the elements themselves—water, mountain, sky, rock, wave—to speak without decorative interventions.

Gea ultimately proposes a different relationship with the natural world—one based not on possession or spectacle, but on contemplation and immersion. By showing us the earth and the ocean in their less accessible versions, and by emphasizing the ephemerality of human presence against the permanence of geological and oceanic processes, these images leave space for reflection on our place within—rather than above—the living systems we inhabit. Beauty here is not comforting but clarifying, reminding us of scale, time, and our own temporality within the vast continuity of the planet itself, as we rediscover our place within it with greater mindfulness and sensitivity.